Pallas, only-begotten, venerable offspring of the great Zeus…

wisdom, ever-changing forms, huge female serpent…1

Orphic Hymn to Athena

One would hardly think of the radiant daughter of Zeus upon hearing the term “Snake Goddess.” Instead, the mind travels to much more ancient deities, such as the serpent-holding, bare-breasted figurines of Minoan Crete, dating from approximately 1600 BCE. These were most probably manifestations of the Goddess of Nature, perhaps related to Gaia, the Earth Mother, whose sons often took the form of large reptiles. “What could be further removed from the protectress of Athens?” one might think.

A goddess of wisdom and justice, a warrior and mentor of heroes, Athena seems detached from the chthonic world associated with the snake and the earth. Yet, for some reason, serpents often seem to crawl on or next to her youthful, strong body. In fact, they are an integral part of her iconography. They frequently emerge from her aigis cloak, which was also adorned with the monstrous head of the snake-haired Gorgon.

Moreover, the colossal gold and ivory statue of Athena Parthenos, made by the famous sculptor Pheidias around 440 BCE, featured a large serpent rising from the ground and resting against the inner side of her shield. This masterpiece once decorated the goddess’ most renowned temple, the Parthenon on the Acropolis of Athens. Today we can get a glimpse of what this amazing work of art must have looked like through a much smaller marble copy of it, the Varvakeion Athena Parthenos.2 An impressive modern replica of Pheidias’ sculpture can be seen in the Nashville Parthenon, in Tennessee.

What was this mysterious snake that has such a prominent place next to the goddess? Pausanias the traveler sheds some light on the matter: it is probably Erichthonius, he claims.3 Few people today have ever heard of this obscure figure, one of the mythical early kings of Athens. Yet, his story brings Athena in close proximity with an older world of magical transformations:

Athena came to Hephaestus, desirous of fashioning arms. But he, being forsaken by Aphrodite, fell in love with Athena, and began to pursue her; but she fled. When he got near her with much ado (for he was lame), he attempted to embrace her; but she, being a chaste virgin, would not submit to him, and he dropped his seed on the leg of the goddess. In disgust, she wiped off the seed with wool and threw it on the ground; and as she fled and the seed fell on the ground, Erichthonius was produced. Him Athena brought up unknown to the other gods, wishing to make him immortal; and having put him in a chest, she committed it to Pandrosus, daughter of Cecrops, forbidding her to open the chest. But the sisters of Pandrosus opened it out of curiosity, and beheld a serpent coiled about the babe; and, as some say, they were destroyed by the serpent, but according to others they were driven mad by reason of the anger of Athena and threw themselves down from the acropolis. Having been brought up by Athena herself in the precinct, Erichthonius expelled Amphictyon and became king of Athens; and he set up the wooden image of Athena in the acropolis, and instituted the festival of the Panathenaea [in her honor].4

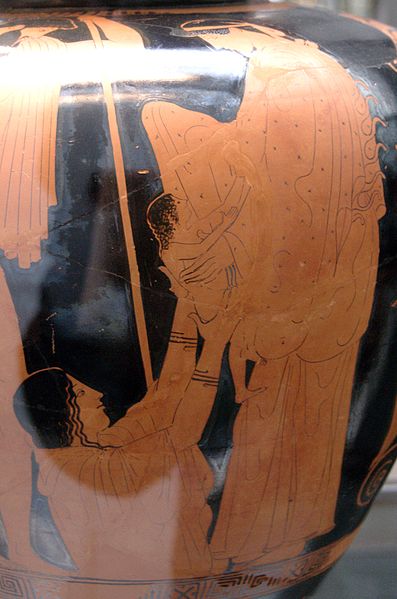

According to a common interpretation, Erichthonius’ name comes from erion, “wool”, and chthon, “earth,” which is another name of Gaia.5 It’s far from surprising then that in ancient vases Gaia herself is shown emerging from the ground, offering her baby son to the virgin goddess.6 Virgin? Not necessarily so. True, her chastity is often emphasized in ancient texts, yet the Greek word parthenos (“virgin”) originally simply meant “unmarried woman.”7

George Derwent Thomson, an older scholar of classical studies, has proposed an intriguing theory: since Athena is closely associated with serpents, she may have originally been herself the mother of Erichthonius, who according to some ancient writers said was half-human and half-snake.8 Perhaps the myth of his bizarre birth was invented at a later time when the physical virginity of women (and goddesses) had become a primary concern in society.9 Thomson also points out the possible connection between Athena and the Minoan Snake Goddess, which has also been noted by other scholars, like Arthur Bernard Cook and David Reid West.10

Today, one might cringe at the thought of assigning the protection of an infant to a snake as Athena did. To the modern mind, the serpent is associated with lethal poison, danger, and evil. Yet in Greece, very few snakes are poisonous. With the notable exception of the viper, all other species are considered totally harmless and occasionally, can even make themselves useful by eating mice.

The Sacred Serpent

Strange as it may seem, Hellenic mythology reveals a true fascination with the serpent. Large snakes (called drakontes, “dragons”) are sometimes portrayed as destructive forces that end up killed by gods and heroes, like Apollo and Heracles. At the same time, though, the serpent frequently appears benign, even sacred, in close association with the Underworld and various divine figures.

Athena’s snakes seem to have protective qualities, just like the reptilian sons of Gaia were often the guardians of a special place. One of the Acropolis temples was the home of a real, live snake dedicated to the goddess of wisdom. This temple was called Erechtheum, in honor of Erechtheus, another mythical king of Athens who, not by accident, was closely related to Erichthonius. The creature that lived there was known as oikouros ophis, “the home-guarding snake.” Hesychius of Alexandria says that it was considered the guardian of the Acropolis and was fed pies made with honey.11

Plutarch narrates a telling story that reveals the significance of the sacred serpent: in one of the Persian invasions in the early 5th century BCE, the Athenian general Themistocles was trying hard to persuade the citizens to abandon the city before it was destroyed by the enemy, who largely outnumbered the Athenian army. That was no easy task, thus he resorted to a trick: when the priests of Athena reported that the guardian of the homeland had disappeared leaving their daily offerings of food untouched, he interpreted this as a divine sign. It meant, he said, that the goddess herself had left the city, pointing the way to the sea.12 The trick worked—the Athenians embarked on their ships, the women and children were brought to the island of Salamis, and one of the greatest battles in European history was fought and won.

Interestingly, the concept of the snake as the guardian of the home has survived in modern Hellenic folklore. In many rural parts of Greece, people would allow a snake to live in or around their house and would even feed it sometimes. It was considered a protective spirit which would ensure the health and happiness of the family.13

If we take into account this view of the serpent, then it’s hardly surprising that it was so closely associated with Athena. She herself was a powerful goddess, charged with the protection of heroes and the defense of the city. At the same time she had a number of other qualities, one of which is of particular interest here: she was also considered a healing deity, hence one of her titles was Hygieia, “Health.”

Hygieia was at the same time the name of one of the daughters of Asclepius, the patron of doctors. Does it come as a big surprise that both Hygieia and her father were almost always accompanied by snakes? In fact, the rod of Asclepius, a snake-entwined staff, is a widely accepted symbol of medicine today. Perhaps it’s not a coincidence that one of his sanctuaries, dating to around 420 BCE, is located on the south slope of the Athens Acropolis.

In fact, the healing aspect of the city goddess, Athena Hygieia, was also honored on the sacred hill. Plutarch has preserved for us one more intriguing story, explaining why Pericles, the famous ruler of Golden Age Athens, set up a statue of hers while the Parthenon was being built:

One of the artificers, the quickest and the handiest workman among them all, with a slip of his foot fell down from a great height, and lay in a miserable condition, the physicians having no hope of his recovery. When Pericles was in distress about this, the goddess appeared to him at night in a dream, and ordered a course of treatment, which he applied, and in a short time and with great ease cured the man. And upon this occasion it was that he set up a brass statue of Athena Hygieia in the citadel near the altar, which they say was there before.14

We do not know what this statue looked like, but it is safe to assume that the serpent’s mysterious presence must have been part of it. The goddess Hygieia was frequently depicted as a young, beautiful woman feeding a drakon, a large snake wrapped around her body. Even as late as the 2nd century CE, the statues of both Hygieia and Athena Hygieia stood near the entrance to the Acropolis.15

From the time of the Minoan Snake Goddess until late antiquity, the eerie charm of the serpent is ever-present. Its ability to renew its skin certainly played a role in the healing qualities attributed to it. Its old skin was called geras by the Greeks, a word that also meant “old age.”16 In their eyes it must have embodied the powers of renewal and regeneration. Its close contact to the earth—and the wise old Earth Mother, Gaia—would also have contributed to its powerful aura.

Athena, one of the most significant figures of the Hellenic pantheon, inherited the connection to this sacred creature. As she carried the symbol of her venerable great-grandmothers on her body, she must have seemed imbued with the life and blood of these primordial feminine forces.

The text is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

If you enjoyed this essay, please share it on social media. You are welcome to let me know what you thought about it in the comments below. You may also like to read the essays “Hagia Sophia and the Goddess of Wisdom” and “Orphic Mysteries and Goddess(es) of Nature.”

Notes

- Orphic Hymn 32, 1, 10-11, translated by the author. ↩︎

- Date: 2nd-3rd c. CE, National Archaeological Museum, Athens, Greece, Catalogue Number: Athens NM 129. ↩︎

- Pausanias 1.24,7. ↩︎

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 3.14,6. Translated by Sir James George Frazer, Apollodorus, The Library, Loeb Classical Library, vol. 121 & 122 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; London: William Heinemann, 1921). Online at Apollodorus, Library 3, http://www.theoi.com/Text/Apollodorus3.html. ↩︎

- Some ancient writers derived the first component of Erichthonius’ name from eris (strife) while others from erion (wool). See note 296 in Apollodorus, Library, 3.14,6, by Frazer, http://www.theoi.com/Text/Ap3d.html#296. ↩︎

- One example is an attic red-figure stamnos, dated at 470–460 BCE, painted by Hermonax, currently in the Staatliche Antikensammlungen (State Collections of Antiques) in the Kunstareal of Munich. ↩︎

- H. G. Liddell, and Robert Scott. Great Dictionary of the Greek Language, translated by Xenophon P. Moschos (Athens: Ioannis Sideris), s.v. “parthenos.” ↩︎

- Pseudo-Hyginus, Fabulae 166. ↩︎

- George Derwent Thomson, Studies in Ancient Greek Society: The Prehistoric Aegean, vol. 1, trans. Yiannis Vistakis (Athens: Kedros, 1989), 181 (originally published in London by Lawrence & Wishart, 1949). ↩︎

- A. B. Cook, Zeus: A Study in Ancient Religion, Vol. 3, Part 1 (Cambridge, 1940), 189, cited in David Reid West, Some Cults of Greek Goddesses and Female Daemons of Oriental Origin, (dissertation submitted for the degree of PhD, University of Glasgow, 1986-1990), 169. West agrees with Cook (ibid., 170). ↩︎

- Hesychius, Dictionary, s.v. “oikouros ophis.” ↩︎

- Plutarch, Themistocles 10.1. A similar story is told by Herodotus 4.38-41. ↩︎

- G. A. Megas, Greek Festivals and Folk Customs (Athens, 1957), 14. ↩︎

- Plutarch, Pericles 13.8. ↩︎

- Pausanias 1.23,4. ↩︎

- Liddell and Scott, Great Dictionary, s.v. “geras.” ↩︎